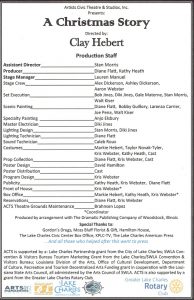

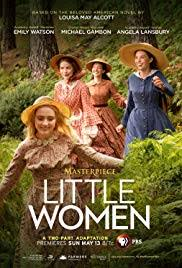

AUDIO OPTION FOR REVIEW OF LITTLE WOMEN – GERWIG STYLE

SHORT TAKE:

Well told but fatally flawed as its ultimate intent is to brutally undercut the original theme of the classic story with a harsh feminist agenda.

WHO SHOULD GO:

Adults ONLY for its twisted theme revealed at the end of the movie.

LONG TAKE:

This 2019 version of Little Women, by extremely talented director/adaptor Greta Gerwig (Ladybird SEE REVIEW HERE), is the latest of 3 in three years based upon the titular novel. These three latest are only a few of many versions available on celluloid. There are LOTS more, including the 1994 version with none other than Batman’s Christian Bale in the role of Laurie and Stranger Things rehabbed Winona Ryder as Jo – but that would be a review for another time.

This 2019 version of Little Women, by extremely talented director/adaptor Greta Gerwig (Ladybird SEE REVIEW HERE), is the latest of 3 in three years based upon the titular novel. These three latest are only a few of many versions available on celluloid. There are LOTS more, including the 1994 version with none other than Batman’s Christian Bale in the role of Laurie and Stranger Things rehabbed Winona Ryder as Jo – but that would be a review for another time.

SPOILERS – EVEN FOR THOSE FAMILIAR WITH THE STORY

Little Women is based upon the classic children’s novel of the same name, about the Marches, a family of four girls and their mother living in Massachusetts on very moderate funds during the Civil War waiting for the family patriarch chaplain to return from the front lines. Included in the cast are the March’s very wealthy maiden Aunt March, their rich neighbor Mr. Laurence and their pitifully poor neighbors, the Hummels.

This 2019 Little Women tells the tale in period costume.

This 2019 Little Women tells the tale in period costume.  However, the 2018 version told in modern day is far far closer to the book’s original theme and intent. The author of the source material, Louisa Mae Alcott had a very unpleasant childhood of poverty under the hands of a tyrannical and irresponsible penniless spendthrift father. Louisa became the breadwinner of the family in part due to her writing of this classic story, idealistically shaped from her wretched family life. Alcott’s autobiography would have been fascinating. Another retelling of Alcott’s story would have been lovely.

However, the 2018 version told in modern day is far far closer to the book’s original theme and intent. The author of the source material, Louisa Mae Alcott had a very unpleasant childhood of poverty under the hands of a tyrannical and irresponsible penniless spendthrift father. Louisa became the breadwinner of the family in part due to her writing of this classic story, idealistically shaped from her wretched family life. Alcott’s autobiography would have been fascinating. Another retelling of Alcott’s story would have been lovely.

Unfortunately, Ms. Gerwig strove to have her reality and fake it too. We, members of the audience, are lead to believe the woman we see in the beginning of the movie is Jo.  In fact, we find out at the end, she is Alcott, who holds in contempt the values of marriage which she is “forced” to insert into her book to get it published. This attitude is not only offensive but a sucker punch to everyone who went to see Little Women or, worse, unwittingly brought an innocent girl to view what should have been a delightful retelling of this classic.

In fact, we find out at the end, she is Alcott, who holds in contempt the values of marriage which she is “forced” to insert into her book to get it published. This attitude is not only offensive but a sucker punch to everyone who went to see Little Women or, worse, unwittingly brought an innocent girl to view what should have been a delightful retelling of this classic.

That being said, and before I get to the ugly parts of the movie, the acting was splendid. Everyone did an excellent job. Notable were:  Chris Cooper (recently in A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood SEE REVIEW HERE) is terrific as Mr. Laurence.

Chris Cooper (recently in A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood SEE REVIEW HERE) is terrific as Mr. Laurence.  Timothee Chalamet (victimized in the pedophile advocating Call me by Your Name SEE REVIEW HERE) is heartbreaking as Laurie.

Timothee Chalamet (victimized in the pedophile advocating Call me by Your Name SEE REVIEW HERE) is heartbreaking as Laurie.

And Meryl Streep’s Aunt March stole every scene she was in. Streep was the perfect subtle combination of blunt and cynically gruff personality, offering criticism freely and offering no holds barred advice but hiding a genuine affection for her poor relatives about whom she is impatient and condemnatory of what she sees as their poor life choices,

And Meryl Streep’s Aunt March stole every scene she was in. Streep was the perfect subtle combination of blunt and cynically gruff personality, offering criticism freely and offering no holds barred advice but hiding a genuine affection for her poor relatives about whom she is impatient and condemnatory of what she sees as their poor life choices,  but about and for whom she cares deeply.

but about and for whom she cares deeply.

The cinematography by Yorick Le Saux is gorgeous – evoking the soft feel of two hundred years ago yet inserting bright colors to prevent any feel of drabness.

Alexandre Desplat is no stranger to writing soundtracks for off-the-wall movies, writing for bizarrely fascinating Isle of Dogs (SEE REVIEW HERE), the offensive Shape of Water (SEE REVIEW HERE), the eccentric Valerian and The City of a Thousand Planets (SEE REVIEW HERE). And he doesn’t disappoint here, constantly evoking the feel of young women running or dancing, using a variety of instruments to color the moment.

But all of these positives could not offset the serious negatives of this movie.

Instead of being honest about an eventual “reveal” that the woman we have been watching is not Jo, the character, but Alcott the author, Gerwig has Alcott masquerade as Jo.  But in the end Gerwig has “Jo” remain a spinster, complain that she is forced to “sell” her heroine into marriage to sell her book, and insert a “fantasy” scene which portrays an idealized ending to her book in what can only be described as a backhanded, sarcastic middle finger to the audience, as though demonstrating how far Alcott had to condescend to the masses to get her genius in print – that a happy ending with marriage and family is merely a trite and commonplace mechanism with which to make money, not a noble example of what millenia of people have found to be a blessing.

But in the end Gerwig has “Jo” remain a spinster, complain that she is forced to “sell” her heroine into marriage to sell her book, and insert a “fantasy” scene which portrays an idealized ending to her book in what can only be described as a backhanded, sarcastic middle finger to the audience, as though demonstrating how far Alcott had to condescend to the masses to get her genius in print – that a happy ending with marriage and family is merely a trite and commonplace mechanism with which to make money, not a noble example of what millenia of people have found to be a blessing.

Ms. Gerwig was true to neither the classic nor to what could have been an autobiographical historic drama. Given that so many versions of Little Women have come out recently it would have made sense to go complete bio and tell the story, not of Jo again, but of Louisa Mae Alcott and her sisters.  Alcott’s sisters closely mirrored her literary characters. Elizabeth (Beth) did indeed die young. Youngest sister May (anagrammed into Amy) married, not the boy next door, but a businessman violinist. Anna (Meg) married one John, not Brooke, but Pratt who, like Mr. Brooke died unexpectedly young and not that well off.,

Alcott’s sisters closely mirrored her literary characters. Elizabeth (Beth) did indeed die young. Youngest sister May (anagrammed into Amy) married, not the boy next door, but a businessman violinist. Anna (Meg) married one John, not Brooke, but Pratt who, like Mr. Brooke died unexpectedly young and not that well off.,

Ms. Gerwig placed one foot firmly in the familiar tale and the other in reality just enough to makes smarmy digs at the notion that women “had” to marry to be able to support themselves.  Given Alcott’s success, this was obviously not entirely true, and only succeeded in making the March girls hypocritical and tipping Ms. Gerwig’s condescending hand towards the institution of marriage. Shoehorning political correctness into this otherwise lovely tale is unbecoming of this otherwise talented director.

Given Alcott’s success, this was obviously not entirely true, and only succeeded in making the March girls hypocritical and tipping Ms. Gerwig’s condescending hand towards the institution of marriage. Shoehorning political correctness into this otherwise lovely tale is unbecoming of this otherwise talented director.

Had she wanted to tell an honest tale of Ms. Alcott’s life story I think that would have been a far more worthy effort than to create a mish mash blend of reality and fiction that satisfied and did no true justice to either tale or genre.

There is much to commend this latest vision. But easy accessibility is not one of its virtues. This is Little Women: intermediate studies level. If you are not completely familiar with the story, you could easily get lost. The movie starts near the end of the story as “Jo” (who later turns out to really be Alcott but going by Jo) is in New York trying to get her stories published. Beth is already dying. Mr. Bhaer’s interest and honest friendship are going mostly unnoticed and unappreciated.  The story then jumps back and forth, not only from there to Jo’s early life with her family in flashbacks, but back and forth between the script as written based upon the classic novel and “reality” as Jo changes her story while negotiating with her would be publisher, “shoehorning” in a love story for herself to make the book more marketable, which life event did not really happen. Alcott actually died a spinster.

The story then jumps back and forth, not only from there to Jo’s early life with her family in flashbacks, but back and forth between the script as written based upon the classic novel and “reality” as Jo changes her story while negotiating with her would be publisher, “shoehorning” in a love story for herself to make the book more marketable, which life event did not really happen. Alcott actually died a spinster.

Even if you ARE familiar with the story it will be very confusing. The characters are not identified right away so who they are gets muddled and is not aided by the frequent flashbacks. It is an interesting though ultimately very flawed perspective. Our family studied it while homeschooling, saw multiple versions over the years and even appeared as a family at a local community theatre production of the stage play. So I know the story well but still had to pay attention to be sure I got the characters right.

There are incongruities which are relatively trivial but VERY distracting. For example, the actresses’ ages chronologically match up to their respective March characters, but they don’t LOOK the right ages. The girl who plays Amy, Florence Pugh, LOOKS and acts the oldest but plays the youngest March. Emma Watson’s Meg (the oldest March girl) looks and acts as young as Amy should be.  The actor playing Mr. Bhaer, Louis Garel, is 9 years older that Saiorse Ronan (Jo), but looks Ronan’s (Jo’s) age. He SHOULD look and act about 15 years older than Jo.

The actor playing Mr. Bhaer, Louis Garel, is 9 years older that Saiorse Ronan (Jo), but looks Ronan’s (Jo’s) age. He SHOULD look and act about 15 years older than Jo.

Attributed to everyone from Samuel Goldwyn to Humphrey Bogart, referring to people who want to propagandize movies, is the statement: “If you want to send a message, call Western Union.” Whoever said it first, Ms. Gerwig did not get the memo and has decided to create a hit piece on men and marriage in general and the themes of Little Women in particular.

Ms. Gerwig made the men as weak as possible.  When Odenkirk’s pathetic Mr. March finally makes his appearance, far from the joyous relief of having their strong male protector back, as he should have been, I had the overwhelming impression that he was just going to be another weak dependent mouth for Marmee to somehow have to find a way to feed. In Bart Johnson’s Mr. March from 2018’s Little Women

When Odenkirk’s pathetic Mr. March finally makes his appearance, far from the joyous relief of having their strong male protector back, as he should have been, I had the overwhelming impression that he was just going to be another weak dependent mouth for Marmee to somehow have to find a way to feed. In Bart Johnson’s Mr. March from 2018’s Little Women  we see the backbone from which all these Little Women get their strength.

we see the backbone from which all these Little Women get their strength.

While it is understandable that Alcott would have experienced the Odenkirk version, she WROTE the Johnson version into her book – the man she likely would have wanted to be her father. But Gerwig, again, wants to merge the two to destroy the beautiful story Alcott wrote and simultaneously muddles her opportunity to tell a more true to life biography by awkwardly merging Alcott’s ugly truth with Alcott’s beautiful written literary vision.

Gerwig also made the sisters appear very cold and Machiavelian at times. As the three surviving sisters walk through the recently deceased Aunt March’s spacious home, which she has generously bequeathed to Jo, all Jo says is that she thought Aunt March didn’t like her, to which Amy comments she can dislike Jo and still give her the house.

Gerwig also made the sisters appear very cold and Machiavelian at times. As the three surviving sisters walk through the recently deceased Aunt March’s spacious home, which she has generously bequeathed to Jo, all Jo says is that she thought Aunt March didn’t like her, to which Amy comments she can dislike Jo and still give her the house.

The sisters never mention how, despite their Aunt’s cold exterior,  Aunt March was incredibly philanthropic toward them, took Amy on a trip which secured her marriage to Laurie, invented work for the girls with which Aunt March could give the family money and retain their dignity, paid for Meg’s wedding despite her own misgivings about the wisdom of the marriage, and for all the many other generosities she surely provided her poor brother’s family. None of the things Aunt March did for them were mentioned, only a cool assessment of what she could still do for them now that she was dead.

Aunt March was incredibly philanthropic toward them, took Amy on a trip which secured her marriage to Laurie, invented work for the girls with which Aunt March could give the family money and retain their dignity, paid for Meg’s wedding despite her own misgivings about the wisdom of the marriage, and for all the many other generosities she surely provided her poor brother’s family. None of the things Aunt March did for them were mentioned, only a cool assessment of what she could still do for them now that she was dead.

Even worse, the faith in God upon which the Marches relied in the book was given little and nebulous short shrift lip service in this version.

Miss Gerwig is more intent on propaganda than telling a good story. Along with her obvious distaste for, dismissal of and contempt for men, she doesn’t seem to like America much either.

Mrs. March (Laura Dern) volunteers at the Civil War equivalent of the USO. This was only shown once and then only to provide a vehicle for a propagandistic hit piece as Mrs. March expresses how ashamed she is of her country, despite the fact it is literally bleeding to near death to make amends for its sins. This horrifying comment was not in the book. The only time anyone mentioned being ashamed in the book was of themselves for a fault or NOT being ashamed of hard work.

Mrs. March (Laura Dern) volunteers at the Civil War equivalent of the USO. This was only shown once and then only to provide a vehicle for a propagandistic hit piece as Mrs. March expresses how ashamed she is of her country, despite the fact it is literally bleeding to near death to make amends for its sins. This horrifying comment was not in the book. The only time anyone mentioned being ashamed in the book was of themselves for a fault or NOT being ashamed of hard work.

At one point Amy tells Jo that Jo’s writing about something makes it important, explicitly saying that things do not have inherent importance in and of themselves. This is the acme of hubris on Ms. Gerwig’s part. Apparently Miss Gerwig believes things are not relevant or of any significance unless they come out of the mouth of people like her – the professional writers who believe they can shape the world, not by proof or truth or real life experience, not by faith in God or inherent credibility, or common sense. Gerwig believes that truth comes only from the pen of those, like her, who have a self-assessment of their own importance. This is the essence of Fake News.

Ms. Gerwig has also decided on a PC perception of Jo as androgynous. Some on the left have even, fairly, interpreted many of the lines and attitudes Ms. Gerwig injected into Jo’s character as lesbian. Had Miss Gerwig wanted to examine that possibility concerning the author’s lifestyle in a legitimate adult oriented biography, I would have found that appropriate, interesting, and potentially insightful. But to distort Jo, the Jo from the source material this way, in this skewed version of Little Women is propaganda of the most base nature, inappropriately forcing an alternate sexual topic onto a children’s classic character.

Ms. Gerwig has also decided on a PC perception of Jo as androgynous. Some on the left have even, fairly, interpreted many of the lines and attitudes Ms. Gerwig injected into Jo’s character as lesbian. Had Miss Gerwig wanted to examine that possibility concerning the author’s lifestyle in a legitimate adult oriented biography, I would have found that appropriate, interesting, and potentially insightful. But to distort Jo, the Jo from the source material this way, in this skewed version of Little Women is propaganda of the most base nature, inappropriately forcing an alternate sexual topic onto a children’s classic character.

So in conclusion, instead of either a faithful adaptation of the classic novel or an honest and what would have been truly fascinating examination of the real Miss Alcott’s life, Miss Gerwig has decided to work a classic children’s tale into a propaganda project of extreme feminism, anti-Americanism, and manifesto for alternate sexual lifestyles.

And for Miss Gerwig to present the story as an inextricable combination of the fact with the fiction with no disclaimer or delineation between the two, demonstrates that she wanted to have her credibility and fake it too.

Watch the far more delightful, faithful and faith FILLED 2018 version of Little Women instead.