SHORT TAKE:

Golden Age Hollywood film of a torrid affair between a transformed Ugly Duckling and a married man.

WHO SHOULD WATCH:

Mid-teens and up, with parental discussion, for morally ambiguous rationalizations, rejection of children, mental illness, frequent smoking, and adulterous behavior, though absolutely nothing but a bit of kissing is shown. Besides which younger kids would be bored spitless.

LONG TAKE:

SPOILERS!

It is a commonly held misconception that old movies were compasses for morality. This myth is reinforced by the sadly defunct Hays Code and the largely ignored MPAA rating system, not to mention the creation of the Disney empire in the 1920’s, which used to be the Gold standard for family friendly fare. Then there was the preponderance of extremely popular morally upright movies which endorsed and respected religion and marriage, which were released in the 1940’s, 1950’s and 1960’s, such as:  The Ten Commandments,

The Ten Commandments,  Bells of St. Mary’s,

Bells of St. Mary’s,  Parent Trap, Going my Way, Angels with Dirty Faces,

Parent Trap, Going my Way, Angels with Dirty Faces,  Sound of Music and Song of Bernadette.

Sound of Music and Song of Bernadette.

So it is understandable that audiences seeking entertainment less likely to offend a drunken sailor than the average TV show or random choice at a local theater would look to what are considered old classics – relying on the myth that movies made just before, during and right after World War II would aspire to a higher standard of morality than an early morning staggering Bourbon Street denizen. That old classic movies were — classy.

I hate to be the one to disabuse you of this illusion but…they were often – not.

Don’t get me wrong. I love old classics and I highly recommend them – with cautions. I’ve oft mentioned to our kids that it isn’t so much that movies, by and large, were made BETTER a long time ago than they are today, it’s just that the ones we still watch today were the “cream of the crop”, the ones which would, naturally stand the test of time. There were then, just as there are now, MORE than a fair share of stinkers. But, 50 or even 20 years from now, the ones at the theater today, which continue to attract attention later, are likely to be those of an especially high quality of: acting, plot, cinematography, soundtrack, special effects, or a combination. And they will be remembered when others will have been long forgotten.

BUT this does not mean the movies we now remember from 30, 50 or even going on a solid century ago were unerringly squeaky clean or held to a sterling character of righteous behavior.

One such example is Now, Voyager. The title is gleaned from the poem, “The Untold Want” by Walt Whitman (a man not exactly of pristine rectitude himself). The phrase hearkens to the advice given to Charlotte Vale (Bette Davis), the lead character in Now, Voyager by her psychiatrist, (Claude Rains). Charlotte is a drab and emotionally abused spinster, who is sent to go forth and seek adventure and a full life, to “Now, Voyager, sail thou forth, to seek and find.”

This is all well and good as she disentangles herself from her bitter, possessive harpy of a mother (Gladys Cooper) to blossom into a self-respecting beautiful woman. But when she decides to occupy herself on a cruise with the affections of a philandering married man,

This is all well and good as she disentangles herself from her bitter, possessive harpy of a mother (Gladys Cooper) to blossom into a self-respecting beautiful woman. But when she decides to occupy herself on a cruise with the affections of a philandering married man,  Jerry (Paul Henreid) the movie degenerates into a torrid love affair which spends the majority of the rest of the movie rationalizing why he should refocus his affections on the already reconstructed Charlotte who, by all accounts, suffered previously from the same dowdy, ignored life in which Jerry has abandoned his own wife. In other words, why should he spend his time trying to make a beautiful woman out of his own wife when he can forego all that work and effort by exploiting this vulnerable woman at his fingertips. Of course, the answer, resoundingly given by the movie is —- Why NOT?

Jerry (Paul Henreid) the movie degenerates into a torrid love affair which spends the majority of the rest of the movie rationalizing why he should refocus his affections on the already reconstructed Charlotte who, by all accounts, suffered previously from the same dowdy, ignored life in which Jerry has abandoned his own wife. In other words, why should he spend his time trying to make a beautiful woman out of his own wife when he can forego all that work and effort by exploiting this vulnerable woman at his fingertips. Of course, the answer, resoundingly given by the movie is —- Why NOT?

So off Jerry goes with Charlotte, wooing then bedding a more than willing Charlotte. Charlotte justifies her dalliance with a man already taken and with a family, in part, by the knowledge that Jerry’s daughter, Tina, is lonely and unwanted by her own mother, Jerry’s wife. There’s definitely something Freudian or dysfunctionally “Elektra” in Charlotte’s behavior.

Elektra was Oedipus’ daughter, if that gives you a clue. And while this theory is, as Hamlet might say, “more honor’d in the breach,” as it is now universally ridiculed, the Elektra Complex theory was postulated by Carl Jung in 1913 and not yet fully discredited in 1942 when Now, Voyager was released. So there definitely would be a certain armchair psychologist’s nod of understanding, if not approval, by audience members of that time, assuming that Charlotte is taking a certain subtle vengeance on her shrewish and uncaring mother by sleeping with the husband of a woman with a similar personality.

This is not to say it is a badly DONE movie. For its stylized time and manner it is extremely well done. Beautifully tailored costumes, often hand-picked by Bette Davis, herself, for the character of Charlotte; acting which, for that era, was at its height. The extraordinarily and rightly acclaimed Bette Davis and Gladys Cooper won Oscar nominations (back when it meant something), respectively, for best actress, as Charlotte, and best supporting actress, as Charlotte’s horrible mother.

This is not to say it is a badly DONE movie. For its stylized time and manner it is extremely well done. Beautifully tailored costumes, often hand-picked by Bette Davis, herself, for the character of Charlotte; acting which, for that era, was at its height. The extraordinarily and rightly acclaimed Bette Davis and Gladys Cooper won Oscar nominations (back when it meant something), respectively, for best actress, as Charlotte, and best supporting actress, as Charlotte’s horrible mother.

Bette Davis was one of the Grand Dames of Hollywood.  Strong, intelligent, forceful in a largely male dominated industry, she was not at all shy about insisting on her own way of doing things – pressing for changes in everything from script to costuming for the advancement of the film she was in, Davis was a true talent who respected her craft and, like other brilliant later actors such as Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep, did not shy from making herself unattractive for her role. Almost six decades of films include: the literature based

Strong, intelligent, forceful in a largely male dominated industry, she was not at all shy about insisting on her own way of doing things – pressing for changes in everything from script to costuming for the advancement of the film she was in, Davis was a true talent who respected her craft and, like other brilliant later actors such as Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep, did not shy from making herself unattractive for her role. Almost six decades of films include: the literature based  Of Human Bondage and

Of Human Bondage and  The Corn is Green, the filming of stageplays like

The Corn is Green, the filming of stageplays like  Little Foxes and

Little Foxes and  The Whales of August, the psychological horror

The Whales of August, the psychological horror  Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, the expose on the manipulative often meaningless lives of famous actors in

Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, the expose on the manipulative often meaningless lives of famous actors in  All About Eve. From comedy to horror to drawing room romance, there is something for everyone in Ms. Davis’ repertoire of films. And she could convey, with a nod or raised eyebrow, more than many performers today can in five minutes of screen time.

All About Eve. From comedy to horror to drawing room romance, there is something for everyone in Ms. Davis’ repertoire of films. And she could convey, with a nod or raised eyebrow, more than many performers today can in five minutes of screen time.

Paul Heinreid, the noble and self-sacrificing Victor from Casablanca, here is at his subtly slimy best, weaseling his way into Charlotte’s fully consenting bed.

Paul Heinreid, the noble and self-sacrificing Victor from Casablanca, here is at his subtly slimy best, weaseling his way into Charlotte’s fully consenting bed.

Max Steiner won for best music. The black and white filming by Sol Polito makes the most of the gray emotional and moral areas in which the characters live.

And on a personal note it is one of the few movies I’ve seen in which Claude Rains’ character, in this case Dr. Jaquith, Charlotte’s caring psychiatrist, is a completely good guy. His usual fare is the likes of the insane Invisible Man, the evil Earl of Hertford from Prince and the Pauper, the wicked caricature of

And on a personal note it is one of the few movies I’ve seen in which Claude Rains’ character, in this case Dr. Jaquith, Charlotte’s caring psychiatrist, is a completely good guy. His usual fare is the likes of the insane Invisible Man, the evil Earl of Hertford from Prince and the Pauper, the wicked caricature of  Prince John in Errol Flynn’s The Adventures of Robin Hood, and

Prince John in Errol Flynn’s The Adventures of Robin Hood, and  the morally murky Capt. Renault from Casablanca – delightful characters all. But seeing him as a squeaky clean white hat was refreshing.

the morally murky Capt. Renault from Casablanca – delightful characters all. But seeing him as a squeaky clean white hat was refreshing.

So the quality of the production itself was quite high.

But the most troubling part about this whole movie is the way in which the audience is openly being lead and manipulated into a position of accessory guilt to an adulterous affair. We are meant to sympathize with both Charlotte, who knowingly accepts the advances of a married man, and Jerry, a flat out cad, who flirts and schmoozes his way into a vulnerable woman’s arms, justifying his behavior with possibly one of the oldest pickup lines in history: my wife just doesn’t understand me the way you do. While he doesn’t actually say these words, the sentiment is obvious as he parades out an exceptionally unattractive picture of his wife with his two daughters.

But the most troubling part about this whole movie is the way in which the audience is openly being lead and manipulated into a position of accessory guilt to an adulterous affair. We are meant to sympathize with both Charlotte, who knowingly accepts the advances of a married man, and Jerry, a flat out cad, who flirts and schmoozes his way into a vulnerable woman’s arms, justifying his behavior with possibly one of the oldest pickup lines in history: my wife just doesn’t understand me the way you do. While he doesn’t actually say these words, the sentiment is obvious as he parades out an exceptionally unattractive picture of his wife with his two daughters.

What struck me was how much Jerry’s wife reminded me of  pre-transformation Charlotte – dowdy, over-weight, dressed in an unflattering tent, sour expression. And there’s zero excuse for Jerry not to make the same connection, as Charlotte shares

pre-transformation Charlotte – dowdy, over-weight, dressed in an unflattering tent, sour expression. And there’s zero excuse for Jerry not to make the same connection, as Charlotte shares  an old family picture in which Charlotte appears in her most unappealing frumpiness. Jerry even asks, in one of the most indelicate, foot-in-mouth comments in movie history, who the old fat woman is. So the comparison can not have been lost on him: that, if Charlotte can make this physical transformation so complete and that with a bit of love from him can blossom emotionally, why can he not aid his own wife in such a transformation – or at least TRY!

an old family picture in which Charlotte appears in her most unappealing frumpiness. Jerry even asks, in one of the most indelicate, foot-in-mouth comments in movie history, who the old fat woman is. So the comparison can not have been lost on him: that, if Charlotte can make this physical transformation so complete and that with a bit of love from him can blossom emotionally, why can he not aid his own wife in such a transformation – or at least TRY!

The film makers appeared not to have made this connection themselves despite its incredibly blatant obviousness. Jerry could see the swan Charlotte became but refused to see anything but the Ugly Duckling his wife was. I suspect it was because it would have been too much trouble for him to do all that work.

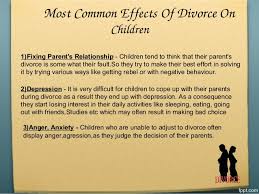

Meanwhile, Charlotte, through a set of happenstances, meets and informally adopts Tina, Jerry’s maternally neglected daughter, transforming Tina from a moody self-loathing adolescent into a happy bubbly child. This is supposed to amend for the diverting of Jerry’s allegiances from his family to herself, his mistress (emotionally, at that point, if not carnally).

Meanwhile, Charlotte, through a set of happenstances, meets and informally adopts Tina, Jerry’s maternally neglected daughter, transforming Tina from a moody self-loathing adolescent into a happy bubbly child. This is supposed to amend for the diverting of Jerry’s allegiances from his family to herself, his mistress (emotionally, at that point, if not carnally).

In the end, Jerry and Charlotte are to remain physically chaste as Dr. Jaquith’s sole contingent proviso for his endorsement of Charlotte’s retention of Tina.

In the end, Jerry and Charlotte are to remain physically chaste as Dr. Jaquith’s sole contingent proviso for his endorsement of Charlotte’s retention of Tina.  In fact, this will become the string by which Charlotte will hold Jerry emotionally hostage for the rest of his life.

In fact, this will become the string by which Charlotte will hold Jerry emotionally hostage for the rest of his life.  To adapt Rhett Butler’s comments to Scarlett about the object of SCARLETT’S infatuation, Ashley Wilkes: [Jerry] can’t be mentally faithful to his wife – and won’t be unfaithful to her technically [aside from that one time in Rio].

To adapt Rhett Butler’s comments to Scarlett about the object of SCARLETT’S infatuation, Ashley Wilkes: [Jerry] can’t be mentally faithful to his wife – and won’t be unfaithful to her technically [aside from that one time in Rio].

As my mother used to say: it takes two to Tango, and I have no doubt that Jerry’s wife was complicit in her own marital undoing. But similarly we are never shown her side of the story either. As Jerry, no doubt, felt unappreciated, Jerry’s wife too would have her own side of the story showing her not to be the sole perpetrator in the murder of their marriage.

I finished the movie noting this was one of the first in a long series of movies intended to assuage the guilty conscience of men who wish to abandon their familial responsibilities in pursuit of a fresh bit of — adventure, the list of which notably includes the most tragic and lamentable Toy Story 4, in which Woody callously walks away from “his” child to chase after Boo Peep’s bustle. SEE REVIEW HERE

Now, Voyager could have utilized the brilliant and deep treasure trove of talent and experience to create a positive and productive tale of the healing of a wounded marriage. Perhaps even through his relationship with Charlotte, learning how to nurture his “hopeless” cause wife into a beautiful woman, as he helped Charlotte, and rekindling his marital relationship with his wife. Instead, though listed among one of the “greats” in cinematic history, this “classic” is just another in a long line of movies without a true moral compass or conscience, justifying the devastation wrought but never seen by a husband and father’s illicit behavior.

Now, Voyager could have utilized the brilliant and deep treasure trove of talent and experience to create a positive and productive tale of the healing of a wounded marriage. Perhaps even through his relationship with Charlotte, learning how to nurture his “hopeless” cause wife into a beautiful woman, as he helped Charlotte, and rekindling his marital relationship with his wife. Instead, though listed among one of the “greats” in cinematic history, this “classic” is just another in a long line of movies without a true moral compass or conscience, justifying the devastation wrought but never seen by a husband and father’s illicit behavior.

CLICK HERE TO PURCHASE ON RUTH INSTITUTE WEBSITE

CLICK HERE TO PURCHASE ON RUTH INSTITUTE WEBSITE