On Golden Pond, playing only this weekend at Central School, is a heart breaking examination of the art of dying. This is a must see performance which, unfortunately, only goes through this weekend. Get tickets at K.C. Productions

WARNING: Some spoilers.

On Golden Pond tells the story of an elderly couple, Ethel and Norman Thayer, performed with chemistry and credibility by  Paula McCain and

Paula McCain and  Randy Partin. The Thayers, given Norman’s deteriorating health, are spending what is likely the last of many summers together at their cabin on Golden Pond, a lake replete with loons and bordered by wild strawberries.

Randy Partin. The Thayers, given Norman’s deteriorating health, are spending what is likely the last of many summers together at their cabin on Golden Pond, a lake replete with loons and bordered by wild strawberries.  Sarah Broussard tackles the challenging role of Chelsea, the Thayer’s unhappy daughter, with skill.

Sarah Broussard tackles the challenging role of Chelsea, the Thayer’s unhappy daughter, with skill.  Matt Dye is charming and funny as Bill, Chelsea’s boyfriend, bringing a sensible lightheartedness to a somber reality.

Matt Dye is charming and funny as Bill, Chelsea’s boyfriend, bringing a sensible lightheartedness to a somber reality.  Brahnsen Lopez is Charlie the quirky and adorable childhood friend of Chelsea. And

Brahnsen Lopez is Charlie the quirky and adorable childhood friend of Chelsea. And  Zachary Benoit, as Bill’s son Billy, who stays with the Thayers for a month, creates a natural bond with Partin’s Norman as his pseudo-grandson.

Zachary Benoit, as Bill’s son Billy, who stays with the Thayers for a month, creates a natural bond with Partin’s Norman as his pseudo-grandson.

The stage is an idealized image of the perfect cabin. Homey, lived in, perhaps even a bit cluttered but warm and friendly with every amenity one could want for a lazy summer fishing camp. And Keith Chamberlain directs this production with style and an eye to keeping this inherently slow paced tale moving in a fascinating interpersonal dance.

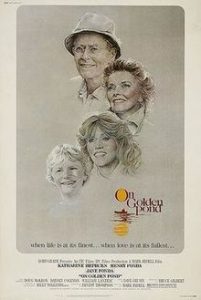

Ernest Thompson, the author of On Golden Pond, has been "eating out" on this play for almost 40 years, earning money from it as a  stage play,

stage play,  then a movie, followed by revivals, even one in 2001 whimsically re-pairing The Sound of Music duo

then a movie, followed by revivals, even one in 2001 whimsically re-pairing The Sound of Music duo

Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer.

Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer.  Thompson even now lives by the lake where the movie was filmed and gives boat tours. With just a little evaluation it quickly becomes pretty obvious this story is biographical.

Thompson even now lives by the lake where the movie was filmed and gives boat tours. With just a little evaluation it quickly becomes pretty obvious this story is biographical.

According to Kelli Allred, PhD, writing for the Southern Utah University Shakespeare Festival, "A self-proclaimed nonbeliever, [Ernest] Thompson writes about lost souls who do not have ‘the luxury of turning to diety,’ so his characters must rely upon one another." In other words, as Thompson does not believe in God, he creates characters who muddle through by depending exclusively on each other. But those characters are ultimately doomed in On Golden Pond to betray that trust, by active neglect of each other, flippant remarks of hurtful rejection, or abandonment by death itself.

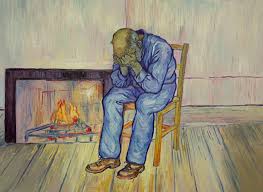

During the play, I was often reminded of Satre’s vision of Hell in No Exit, wherein characters are forced to stay in a room and torment each other with reminiscences of regrets, petty harpings and constant obsession with trivialities. Similarly, the characters in On Golden Pond treat each other to their own versions of Hell. Although free to leave the actual cabin, the characters find the idyllic appearing cabin is a snare net in which the Thayers are trapped either mentally or, in the case of Norman, too frightened by his own deteriorating mental faculties to wander far.

Examples of their self-imposed Hell are rife: Norman repeatedly references death despite the growing distress of his wife, Ethel. Ethel obsesses over loons and strawberries, glossing over their dismal parenting of Chelsea and deliberately ignoring the encroaching dementia and frailty of Norman. As for Chelsea, there is a theater expression immortalized as the title of a play by Elaine Mae: Enter Laughing. With Chelsea it is "enter crying". She drops the temperature every time she responds or is even in proximity to her father. Frowning, hunchbacked, self-admittedly childish, crying and bitter she does not see or communicate with her parents for months on end, and then only to rehash 30 year old hurts.

The author, Ernest Thompson, seems to indicate it is a biography of his own, apparently, dysfunctional relationship with his parents, whose names, Theron and Ester Thompson, echo those of his surrogate family, Norman and Ethel Thayer. Thompson’s father, like Norman, was a school teacher, and Thompson even today, lives quite near the lake where On Golden Pond was filmed. His voice is given to the self-absorbed and depressed Chelsea, the Thayers’ daughter, permanently locked into her own self view as a neglected, underappreciated, fat disappointment. Despite her own adult accomplishments, she acts out her chronic dismay with her father in a string of shallow and unhappy relationships and a dismissal of child bearing.

The spectre of finality sits heavily upon them as 80 year old Norman teases his wife in a constant patter of comments about his own coming demise: comparing himself to her 60 year old doll who might some day either fall or decide to dive into the fireplace, glibly quip how he might not make it all the way down to the end of the driveway, and suggest how his ashes could be sprinkled over her flower garden. Most of the time these observations seem only to torment his wife or perhaps help her face the eventuality she seems determined to avoid thinking about – his departure. But other times his distress is genuine, as in when he gets lost on a familiar path and scurries back to be in the one place he feels safe – by his beloved Ethel.

It is not until the entry of Bill and his son Billy – representatives of the family, wherein the play takes a lighter and more fulfilling turn. Thompson places great emphasis on the point that Chelsea is an only child – grown distant to her parents, an emptiness that is reflected in the preternaturally quiet cabin. Bill and Billy bring a semblance of family which temporarily reignites and renews a certain underlying attentiveness and life in Norman as he takes the boy daily fishing.

Meanwhile, while rejecting a belief in God, Thompson hampers his characters with a formless deistic philosophy. Ethel goes on often about the loons and flowers, as though trying to create a veneer over the fractures in her family. She and Chelsea reminisce about a woodsy campfire group from Chelsea’s youth, associated with an annoying childish song, which repetition stresses the patience of even the easy going Charlie. This emphasis on an idealized artificial relationship with nature suggests that Thompson has a certain deistic belief system – not in God but a ubiquitous "god-ness" in everything – which he substitutes for any truly analytical spiritual life. This semi-spirituality ultimate both proves unsatisfying to the characters and provides no comfort in the moments of crisis which happen during the course of the play. There is no appeal to God and the only references to Him are made as angry interjections but never in prayer.

And although Thompson makes it clear that he does not have any faith in God, neither does he have anything to fill the void which that a-theism creates.

Norman and Ethel demonstrate a philosophy of situational ethics as they shrug their shoulders in a laissez faire attitude when asked by Bill if he and Chelsea, while still unmarried, could sleep together in the cabin. Norman responds with a crude banter which makes it difficult to tell whether he genuinely disapproves or just enjoys shocking his guest, but makes no real effort to establish or enforce any respectful guidelines.

Thompson draws a brilliant portrait of what it is like for someone to face the eventuality of one’s earthly death without the spiritual awareness of a Divine Creator, an immortal soul or a concept of eternity. What is it like for people who think this is all there is? The result for the elderly Thayer couple is one unending day of board (bored) games, Chelsea’s purposeless and childless drifting through relationships, and constant acrimony.

Only when the prospect of acting for the sake of another – for the nurturing of Bill’s son Billy – do they all come together briefly, like cold travelers around a warm fireplace. And for a while they engage with constructive purpose in the world and with each other, healing emotional riffs and coming to an understanding.

It is said: If you can’t be a good example, provide a horrible warning. Norman and Ethel while away their last few days in endless games of Parchessi, listening to Norman’s acerbic "witticisms" and deflecting Chelsea’s angry reproachfulness. Chelsea only finds peace in separation from the shallow and unfulfilling summer cabin life to create a family with Bill and Billy. Near the end, when finally at peace in a real home, Chelsea elicits from her parents a promise we know they will not keep to join her family. Instead, the Thayers literally walk off into the sunset, alone, fully aware they will never come back – death throwing them out of the self-defined Paradise to which they have limited themselves, without hope or prospect of immortality. Neither seeking nor finding any concept of eternity or genuine spirituality, the best Norman can offer Ethel is a passive and bland acceptance of the inevitability of separation, death and oblivion.

The K.C. Productions performance of On Golden Pond deftly and dramatically demonstrates the desperate resignation and shallow accomplishments of facing one’s death without spiritual discernment or faith. Like Satre’s characters they have created their own Hell to which, in the end, they willingly exit.

Peter and Thomas McGregor are in MORTAL COMBAT. We're talking

Peter and Thomas McGregor are in MORTAL COMBAT. We're talking  Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd,

Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd,  Sylvester and Tweety,

Sylvester and Tweety, Tom and Jerry,

Tom and Jerry,  Daffy Duck and Yosemite Sam. Peter is a 5 pound rabbit. Thomas McGregor is a 170 lb 6 foot one inch grown man.

Daffy Duck and Yosemite Sam. Peter is a 5 pound rabbit. Thomas McGregor is a 170 lb 6 foot one inch grown man.

They are trying to EXTERMINATE each other!!! And to see this rabbit get the best of McGregor and watch as McGregor attempts to retaliate is very very funny.

They are trying to EXTERMINATE each other!!! And to see this rabbit get the best of McGregor and watch as McGregor attempts to retaliate is very very funny.

To paraphrase John Cleese from Monty Python's the "Dead Parrot Sketch" Peter and Thomas are trying to enroll each other in the Choir Celestial. They're engaged in attempting to make each other push up daisies. They are trying to introduce each other to our Creator.

To paraphrase John Cleese from Monty Python's the "Dead Parrot Sketch" Peter and Thomas are trying to enroll each other in the Choir Celestial. They're engaged in attempting to make each other push up daisies. They are trying to introduce each other to our Creator.  They are, with great earnestness, endeavoring to KILL EACH OTHER.

They are, with great earnestness, endeavoring to KILL EACH OTHER.

Thomas McGregor tries to chop the bunnies in half with with a hoe! He sets up fatal animal traps in hopes of breaking their necks. His Uncle ATE Peter's father! Peter on the other hand tries to electrocute, trap, and

Thomas McGregor tries to chop the bunnies in half with with a hoe! He sets up fatal animal traps in hopes of breaking their necks. His Uncle ATE Peter's father! Peter on the other hand tries to electrocute, trap, and beat Thomas McGregor to death. At one time he and his friends successfully manage to get the young McGregor to fall off the roof of a two-story house. Had he fallen onto something harder than the turned earth below him it would have been a lethal fall. As it is he is rendered unconscious and the animals all comment about how it will be lovely when the ice cream truck comes to pick him up – referring to the ambulance that came and took away the late Elder McGregor.

beat Thomas McGregor to death. At one time he and his friends successfully manage to get the young McGregor to fall off the roof of a two-story house. Had he fallen onto something harder than the turned earth below him it would have been a lethal fall. As it is he is rendered unconscious and the animals all comment about how it will be lovely when the ice cream truck comes to pick him up – referring to the ambulance that came and took away the late Elder McGregor.

Two males vying, with different but equally compelling motives, for the same woman's affections, try to murder each other in a variety of ways and in the attempt almost succeed! AND, as a side effect, almost kill the young lady as well. Had this not been a child's movie it is likely all three would have ended up dead.

Two males vying, with different but equally compelling motives, for the same woman's affections, try to murder each other in a variety of ways and in the attempt almost succeed! AND, as a side effect, almost kill the young lady as well. Had this not been a child's movie it is likely all three would have ended up dead.

It reminds me of the Monty Python sketch "Self Defense Against Fresh Fruit" where an incompetent self defense instructor explains the fine points of defending oneself against a banana! SEE SKIT HERE

It reminds me of the Monty Python sketch "Self Defense Against Fresh Fruit" where an incompetent self defense instructor explains the fine points of defending oneself against a banana! SEE SKIT HERE

Have the "protestors" never seen what the Three Stooges do to each other?! I have family members with serious food allergies too and I took ZERO offense.

Have the "protestors" never seen what the Three Stooges do to each other?! I have family members with serious food allergies too and I took ZERO offense.  To paraphrase John Adams from the musical 1776 – It's a comedy – you have to offend SOMEBODY!

To paraphrase John Adams from the musical 1776 – It's a comedy – you have to offend SOMEBODY!

set animal traps in beds, electrify door knobs, use slingshots in an effort to emasculate someone with vegetables or blow each other up with dynamite – ALL of which happen in this movie! If you don't want your children seeing this then use a bit of parental discretion and do not go! But don't make the world more peevish and unpleasant for the rest of us.

set animal traps in beds, electrify door knobs, use slingshots in an effort to emasculate someone with vegetables or blow each other up with dynamite – ALL of which happen in this movie! If you don't want your children seeing this then use a bit of parental discretion and do not go! But don't make the world more peevish and unpleasant for the rest of us.

Domhnall Gleeson has appeared in Star Wars as the new and somewhat comedically incompetent baddie, General Hux, occasionally thrown unceremoniously around by a miffed Kylo Ren. He has appeared often with his brothers and father in genres from dark comedy (Calvary) to

Domhnall Gleeson has appeared in Star Wars as the new and somewhat comedically incompetent baddie, General Hux, occasionally thrown unceremoniously around by a miffed Kylo Ren. He has appeared often with his brothers and father in genres from dark comedy (Calvary) to  rom-com fantasy (About Time) to an

rom-com fantasy (About Time) to an  American western (True Grit). He's been shot, tossed, wolf bitten, has murdered his own real life brother as a modern day Cain in Mother! and fallen in love with an android (Ex Machina).

American western (True Grit). He's been shot, tossed, wolf bitten, has murdered his own real life brother as a modern day Cain in Mother! and fallen in love with an android (Ex Machina).

Domhnall's Thomas is as precise in his habits as Phileas Phogg and as cantankerous and anti-wildlife as his rabbit pie eating Uncle. He moves into the MacGreor house with the intention of selling it but the anthropomorphized animals will have none of it. Peter's coat wearing, wise cracking, English speaking rabbit family are as anxious to be rid of this new human interloper as he is of them.

Domhnall's Thomas is as precise in his habits as Phileas Phogg and as cantankerous and anti-wildlife as his rabbit pie eating Uncle. He moves into the MacGreor house with the intention of selling it but the anthropomorphized animals will have none of it. Peter's coat wearing, wise cracking, English speaking rabbit family are as anxious to be rid of this new human interloper as he is of them.

This sets off a series of comical incidents where each side tries to do away with the other all while pretending to be pals for the sake of Bea.

This sets off a series of comical incidents where each side tries to do away with the other all while pretending to be pals for the sake of Bea.

leaps,

leaps,  falls,

falls,

The littlest laughed hardest whenever Pigling Bland appeared to aristocratically gorge himself on whatever happened to be within reach.

The littlest laughed hardest whenever Pigling Bland appeared to aristocratically gorge himself on whatever happened to be within reach.

ninja-like, almost superhuman terror, turning the young MacGregor's modern gizmos back onto his unwary human antagonist.

ninja-like, almost superhuman terror, turning the young MacGregor's modern gizmos back onto his unwary human antagonist.

Thomas would definitely be able to empathize with Elmer Fudd.

Thomas would definitely be able to empathize with Elmer Fudd.

Italian Job, The Great Train Robbery and even Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World; buddy movies like

Italian Job, The Great Train Robbery and even Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World; buddy movies like  The Hitman’s Bodyguard; movies seen from the perps point of view like

The Hitman’s Bodyguard; movies seen from the perps point of view like  Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and  The Sting; mysteries like

The Sting; mysteries like  The Usual Suspect; histories like The Pursuit of DB Cooper and

The Usual Suspect; histories like The Pursuit of DB Cooper and  Serpico; private eye flicks like

Serpico; private eye flicks like  The Maltese Falcon; parable-like such as

The Maltese Falcon; parable-like such as  3 Godfathers or Fargo; ensemble style such as

3 Godfathers or Fargo; ensemble style such as  The New Centurions; pursuit movies like

The New Centurions; pursuit movies like

Blade Runner. Then you have combos. There’s comedy suspense like all the

Blade Runner. Then you have combos. There’s comedy suspense like all the

Minority Report; dark dark comedy seen from the perp point of view like

Minority Report; dark dark comedy seen from the perp point of view like  Dog Day Afternoon; and sci fi comedy mystery like Demolition Man.

Dog Day Afternoon; and sci fi comedy mystery like Demolition Man.

Merrimen (Pablo Schrieber who happens to be the half – brother of Liev "Wolverine’s brother" Schrieber) are planning to pull off the "perfect" heist – snatching the used and soon-to-be shredded hundred dollar bills from the Federal Reserve before they are missed. Schrieber manages this three dimensional anti-hero with the same confident skill with which he played a pure American hero in

Merrimen (Pablo Schrieber who happens to be the half – brother of Liev "Wolverine’s brother" Schrieber) are planning to pull off the "perfect" heist – snatching the used and soon-to-be shredded hundred dollar bills from the Federal Reserve before they are missed. Schrieber manages this three dimensional anti-hero with the same confident skill with which he played a pure American hero in  13 Hours (about the Benghazi embassy terrorist attack).

13 Hours (about the Benghazi embassy terrorist attack).

Gerard Butler’s "Big Nick" who heads up an elite team of police with virtually free rein to keep check on the mayhem in this "Bank Robbery Capital of the World".

Gerard Butler’s "Big Nick" who heads up an elite team of police with virtually free rein to keep check on the mayhem in this "Bank Robbery Capital of the World".

filmed

filmed

PS I Love You as he is the unstoppable secret service agent in the

PS I Love You as he is the unstoppable secret service agent in the

Donnie played by O’Shea Jackson, Jr. Jackson is the son of rapper Ice Cube, and had the rare opportunity to play his own father in

Donnie played by O’Shea Jackson, Jr. Jackson is the son of rapper Ice Cube, and had the rare opportunity to play his own father in

Straight Outta Compton. Jackson does a marvelous job of portraying Donnie in Den, the sympathetic young driver of the gang of thieves.

Straight Outta Compton. Jackson does a marvelous job of portraying Donnie in Den, the sympathetic young driver of the gang of thieves.

not out to create unnecessary mayhem,

not out to create unnecessary mayhem,  there is no doubt Merrimen's group are the bad guys. And though the cops committed more than their share of vice, there is no question Nick's men are the ones who protect the innocent and even attempt to treat their dangerous quarry with dignity. So while endeavoring to show all parties as three dimensional,

there is no doubt Merrimen's group are the bad guys. And though the cops committed more than their share of vice, there is no question Nick's men are the ones who protect the innocent and even attempt to treat their dangerous quarry with dignity. So while endeavoring to show all parties as three dimensional,