AUDIO PODCAST OPTION FOR DISCOVERING CAPTAIN AMERICA IN A MEDIEVAL BOOK ON CHESS

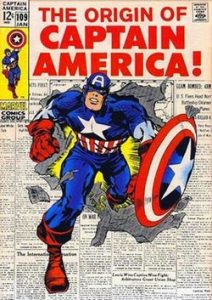

Marvel fans have long been familiar with the figure of Captain America. His conception dates back to the beginning of World War II, 1941, when America needed an example of bravery and fortitude against tremendous odds. I’m sure his creators, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, genuinely believed they were penning a brand new image to inspire a determined America during that time of great peril, as she fought against the evil of tyranny: the Axis in general and Nazis in particular. Inspirational Cap is. Original he is not.

I was doing research for a play set in the Medieval era and came across a book written in 1474 by a man named William Caxton.

I was doing research for a play set in the Medieval era and came across a book written in 1474 by a man named William Caxton.  Caxton is thought to be the first English printer and retailer of printed books and his Game and Playe of Chesse, (and no those are not misspellings but Anglo-Norman English) is believed to be only the very second book ever printed.

Caxton is thought to be the first English printer and retailer of printed books and his Game and Playe of Chesse, (and no those are not misspellings but Anglo-Norman English) is believed to be only the very second book ever printed.

In the book there is a passage which anticipated and described the character we know as Captain America with great precision.

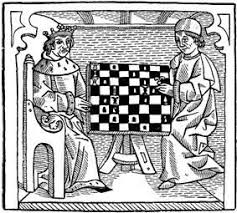

The premise of Game and Playe of Chesse is of a tutor instructing a monarch. By way of guide the tutor explains the ideal virtues of each of the gentry on which the piece is based: fairness of a king, faithfulness of his queen, good judgement of his “alphyns” (which in Old German means chaser or wolf and meant as a reference to a judge, which eventually morphed into the modern day chess token of Bishop).

The premise of Game and Playe of Chesse is of a tutor instructing a monarch. By way of guide the tutor explains the ideal virtues of each of the gentry on which the piece is based: fairness of a king, faithfulness of his queen, good judgement of his “alphyns” (which in Old German means chaser or wolf and meant as a reference to a judge, which eventually morphed into the modern day chess token of Bishop).

Then the description of the idealized knight.

Then the description of the idealized knight.

As a side note, the Anglo-Norman looks strange to the modern eye but with a bit of practice becomes surprisingly easy to parse out. One especially unusual feature is the letter that would soon morph into our familiar “s”,  which, in Anglo-Norman English, looks like a lower case “F” with a shortened cross-bar. I do not have that character on my keyboard, and even if I did I would hesitate to use it without an editorial emphasis of some kind because they are, in the jumble of text letters, at first glance (as well as second and third) very difficult to distinguish from our conventional modern “f”. Therefore, for the purposes of this post, I have indicated that medieval “s” as an italicized “f”.

which, in Anglo-Norman English, looks like a lower case “F” with a shortened cross-bar. I do not have that character on my keyboard, and even if I did I would hesitate to use it without an editorial emphasis of some kind because they are, in the jumble of text letters, at first glance (as well as second and third) very difficult to distinguish from our conventional modern “f”. Therefore, for the purposes of this post, I have indicated that medieval “s” as an italicized “f”.

The knyghtes ought to be ftronge not only of body but alfo in corage. Ther ben many ftronge and grete of body – that ben faint and feble in the herte – he is ftronge that may not be vaynquyfshid and ouercomen – how well that he fuffryth moche otherwhile – And fo we beleue that they that be not ouer grete ne ouer lityll ben moft courageous & befte in batayll.

And my amateur/layman’s translation:

The knight should be strong,  not only in body but in

not only in body but in  courage. There have been many large and powerful men who have been faint and feeble of heart.

courage. There have been many large and powerful men who have been faint and feeble of heart.  But he is strong who can not be vanquished, discouraged or overcome in spirit

But he is strong who can not be vanquished, discouraged or overcome in spirit  no matter how much he suffers.

no matter how much he suffers.  And so we believe it is not the physical size of a man,

And so we believe it is not the physical size of a man,  no matter how big or small, that matters, but that it is those who have courage who will do best in battle.

no matter how big or small, that matters, but that it is those who have courage who will do best in battle.

So, out of history’s echo, comes the prescient description of America’s example of the perfect knight, 467 years before Cap’s first iteration in Marvel Comics.  The physically frail Steve Rogers who,

The physically frail Steve Rogers who,  with the help of Dr. Erskine’s Super Soldier formula, becomes the first Avenger,

with the help of Dr. Erskine’s Super Soldier formula, becomes the first Avenger,  not because of his height or strength, but because of the

not because of his height or strength, but because of the  greatness of his heart – his kindness, his sense of justice, fair play, common decency and courage. And if Cap’s motto while confronting overwhelming odds:

greatness of his heart – his kindness, his sense of justice, fair play, common decency and courage. And if Cap’s motto while confronting overwhelming odds:  “I can do this all day,” doesn’t summarize Caxton’s otherwise flowery prose into a simple and pragmatic maxim, then I do not know what does.

“I can do this all day,” doesn’t summarize Caxton’s otherwise flowery prose into a simple and pragmatic maxim, then I do not know what does.